Ukraine: The Moral Mirror of the 21st Century 🇺🇦

Ukrainian men and women bear a profoundly conflicted identity—divided, fractured, saturated with psychological dissonance. The same Soviet state that exterminated them through hunger during the Holodomor (the genocide perpetrated by Stalin, still not acknowledged by much of the “international community”), that repressed and exploited them, was also the one that shaped them as subjects. The state that killed was, at the same time, the one that provided housing, a wage, and the security of a blue-collar job. That double bond—protector and executioner—left an indelible moral scar on the Ukrainian soul.

This means that Soviet culture, the same that humiliated and starved them, forged Ukraine’s national character, from its infrastructure to its vast institutional corruption—police, universities, hospitals, tax offices. Along with the “modernity of the New Man,” it handed down the most corrupt statistics in Eastern Europe—and without nuclear weapons to show for it, as well as great tragedies.

To be a man or a woman in Ukraine is to inhabit roles pierced by those contradictions, bound to the very etymology of the word Ukraina— “on the border.” It is, in essence, a borderline experience. Today Ukraine once again finds itself torn by the fracture of its national heart: between the woke, progressive West that promises infinite rights and the Eastern Europe that still clings to family, faith, and belonging. It is the old dilemma between the temple and the marketplace, between the cross and the flag of twelve stars. Should it remain a nation with a soul, or become a franchise of global liberalism? Beneath the smoke of war, a moral battle unfolds: Church or eurocracy, identity or dissolution, homeland or performance.

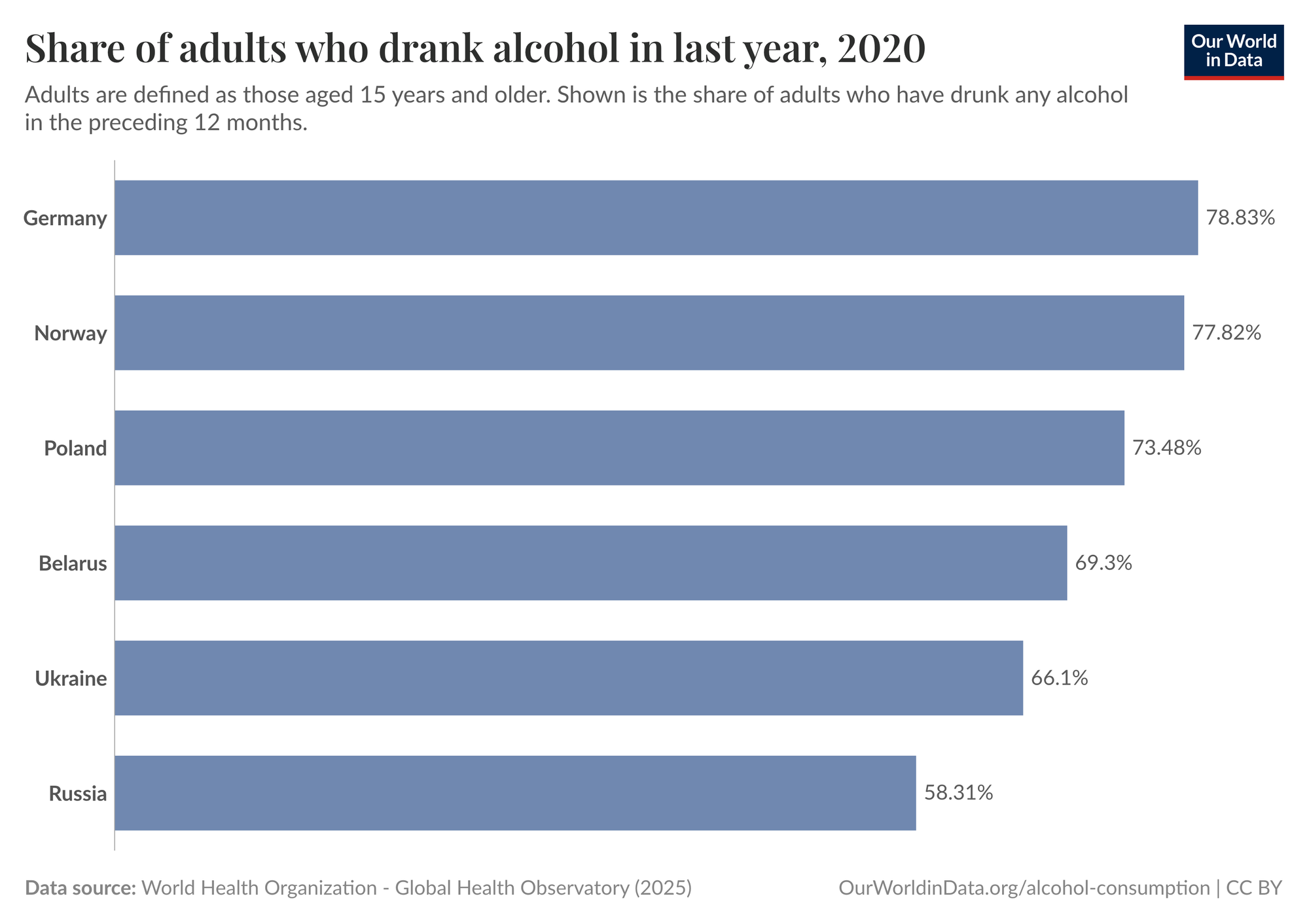

In the Slavic East—Belarus, Russia, Ukraine—there once circulated a folk-psychological cliché: the man as lazy, alcoholic, emotionally unreliable. The eternal “sofa male with a glass of vodka.” In Soviet literature and cinema, the muzhik—that rough, resigned, and perpetually drunk peasant—became the living metaphor for a nation that survived on vodka and fatalism. He was both victim and buffoon: a man crushed by the state, but functional to the heroic myth of popular resistance. Official art needed him as a mirror of proletarian rusticity, and the West, for its part, adopted him as a moral caricature. The “drunken Russian”—and the rest of the Slavs—was exported as an emblem of emotional barbarism and Eastern backwardness: a being without discipline, incapable of self-control, condemned to disorder.

That masculine stereotype, almost a domestic proverb of the post-Soviet era, portrayed the man as purposeless, an idle buffoon—a poor copy of the groomed Western male with euros in his pocket. Then came the war, and the script flipped like a tragicomedy: the same man once mocked for inertia became a national hero, a voluntary martyr, an epic figure who “dies for the motherland.” And the woman—once the symbol of patience and care—became the survivor, the migrant, the strategist, the reinvented girl.

Recent reports on Ukraine (KVINFO, 2023) show that the Russian invasion reinforced binary gender roles: men as defenders and heroes; women as mothers and caretakers. What was once complaint— “they don’t commit”—mutated into exaltation— “they commit to death, what men!” Man was rehabilitated as the patron saint of heroism, and war restored his dignity through its darkest instrument: death.

The stereotype was not erased, merely repainted, now with Zelensky’s signature on the shoulder patch. When it comes to dying on the front lines, there are no patriarchal privileges...

Beneath this mythology of masculine sacrifice, a quieter movement unfolded: female migration. Millions of women crossed into the European Union, many finding in war a departure point to rebuild their lives, though not without contradictions. Some entered relationships with European men who could offer a life in euros; others simply fled. As with every catastrophe, war opens paths to emancipation while multiplying dependencies and transactional bonds. Hence the cruel parable circulating in popular psychology: the woman who awaits word of her husband’s death at the front in order to collect the insurance and flee the country. No serious study yet confirms it as widespread, but its persistence as rumor exposes a sociological truth: male sacrifice can serve female survival—and perhaps even resurrect the old post-Soviet dream.

To understand the background, we must look before the war. Ukraine was already an exporter of female labor, even within the sexual economy. The data speak plainly: according to the European project TAMPEP, Ukraine ranked third or fourth among the main countries of origin for sex workers in Europe. Within Ukraine, organizations such as Legalife and the Alliance for Public Health estimated between 53,000 and 86,000 people engaged in sex work before 2022. Meanwhile, the International Organization for Migration reported that since 1991, over 300,000 Ukrainians—mostly women—had been victims of trafficking, with more than a thousand identified and assisted in 2021 alone.

The roots of this economy reach deeper—back to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. When the planned economy imploded, it didn’t just destroy an ideology—it erased material stability. Overnight, entire regions were plunged into poverty: factories shuttered, state salaries vanished, inflation devoured savings. The “liberation” of the 1990s meant hunger, unpaid bills, and a black market for everything. For many Ukrainian women, survival became an affective border act. They went to Moscow or Western Europe “to seek life,” often falling into domestic servitude, informal labor, or prostitution. It wasn’t vice that moved them, but necessity. They were not symbols of moral decline but of economic displacement—living reminders that freedom without bread is merely another form of exile.

These numbers, far from stigma, trace the empirical geography of an economy where the body becomes a passport. In Western Europe, over 60% of sex workers are foreign-born; in Germany, the figure exceeds 63%, with reports from Die Welt noting that roughly half of Berlin’s sex workers are now Ukrainian (Die Welt, 2024). Structural demand for women from the East meets structural vulnerability of those who leave. Ukraine was part of that flow long before Russian tanks crossed its borders. To speak of it is not defamation—it is comprehension.

War did not erase that market; it transformed it. Today, Ukrainian women—voluntary migrants, refugees, or displaced—navigate between humanitarian aid, precarious jobs, digital economies, dating apps, and, in some cases, transnational sex work. Meanwhile, male sacrifice is measured in grim statistics: Zelensky acknowledged more than 46,000 soldiers killed, while independent estimates reach up to 79,000 dead or missing. Such demographic weight distorts society itself: widows, displaced women, orphans, collapsed household economies. Without men at home, the female role expands—and mutates.

The social drama does not end with gender inversion; it reaches the sphere of power.

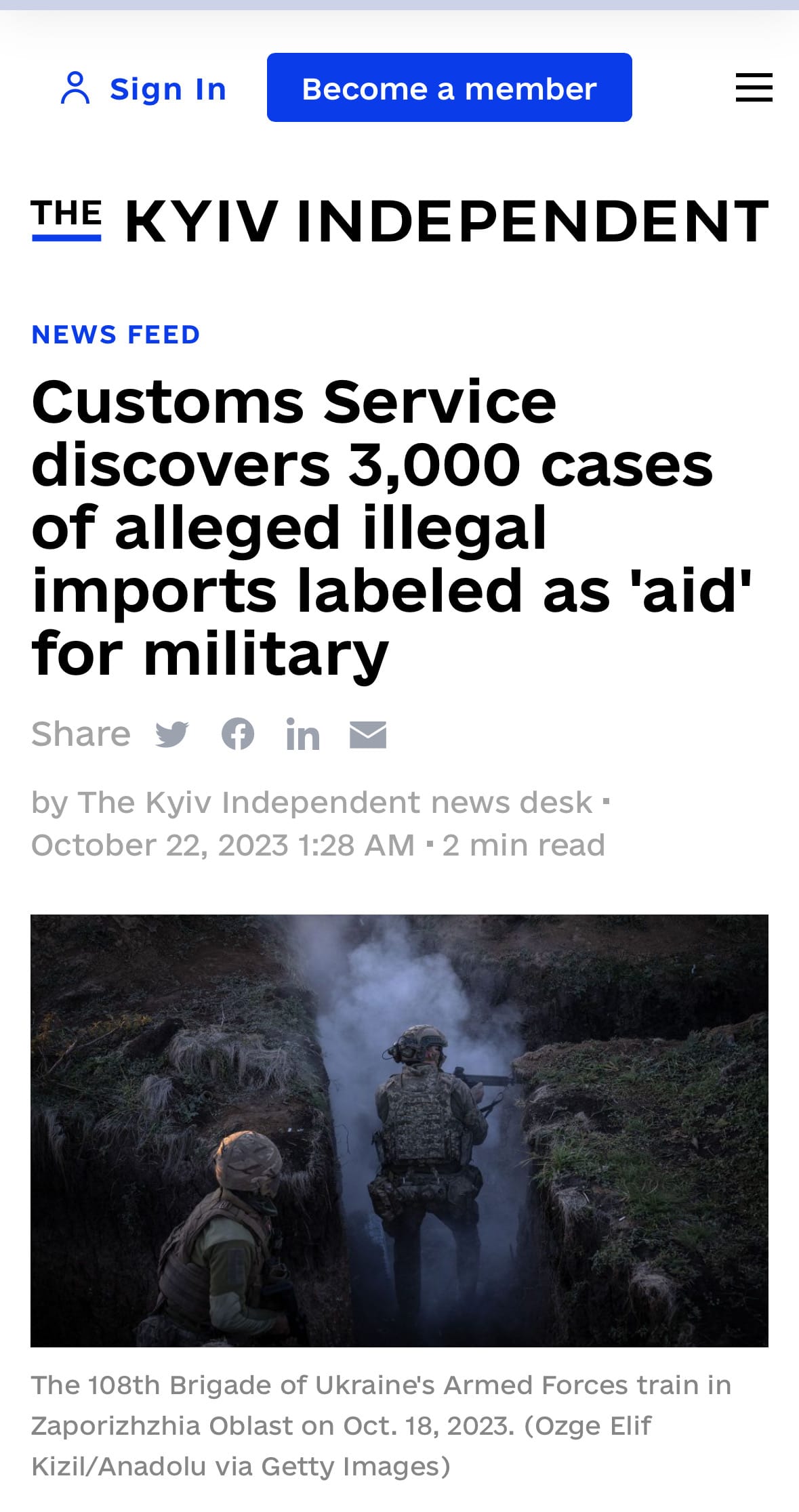

Power in Kyiv is not an altar of virtue but a machine of purification by fire: every crisis promises redemption and ends in redistribution. Zelensky did not become the “billionaire of war” mocked by Russian memes, but neither is he the civic ascetic exported by Netflix. His declarations show fluctuating yet rising income during the invasion—bonds, rents, dividends—and his old offshore network, exposed in the Pandora Papers, remains tattooed on public memory. There are no miracles: an actor-turned-president keeps his bank account safer than most soldiers keep their legs.

What shocks is not the numbers but the moral theatre of power. In 2023, Parliament tried to keep asset declarations secret, and only social pressure and a forced presidential veto averted a blackout of transparency. Two years later, in 2025, another scandalous act: a bill to weaken the independence of anti-corruption agencies, reversed only when international outrage threatened to close the aid pipeline. In between, ministers, MPs, and military-industrial businessmen marched through arrests for bribes and inflated defense contracts, proving that patriotism also trades on the black market.

“Self-pardon”? Nothing so crude. Something more refined: a managed choreography of impunity, where morality is performed while budgets are negotiated. Among ruins and flags, Kyiv still practices the old post-Soviet alchemy—turning collective sacrifice into political capital, and war into opportunity.

Popular psychology, of course, simplifies. Yesterday it said: “Ukrainian men are lazy drunks.” Today: “They are heroes dying for freedom.” Yesterday the woman was the enduring wife; today she is the resilient refugee. The script changes, not the structure: he sacrifices, she adapts. It has always been so. Both remain characters in a system that requires heroes and survivors, martyrs and migrants. The myth of the widow escaping with the military pension is not an insult but a bitter parable of how wartime narratives convert misery into virtue and grief into opportunity.

Meanwhile, social reality needs no adjectives: tens of thousands of dead men; over 80,000 women in sex work before the war; 300,000 victims of trafficking in three decades; millions of displaced women seeking a country that will take them. It is not about judgment but understanding. The male body turned into sacrifice and the female body into mobility are two poles of the same civilizational drama: the instrumentalization of the human being—whether by heroism or by hunger.

And yet, despite the irony of the clichés, the Ukrainian people retain a dignity that resists caricature. There are women who hold families together, who work, volunteer, fight, rebuild villages. There are men who die not for propaganda but because they truly believed in something. Popular psychology cannot digest such ambiguity—it demands saints or villains, heroes or traitors. But reality is messier.

In the end, Ukraine functions as the moral mirror of the 21st century. In this country where the “lazy man” became a martyr and the “submissive woman” became an adventurous migrant, we understand that history does not progress—it merely changes masks. The structures remain: dependency, sacrifice, the glorification of risk. Heroes are recycled, victims re-edited, clichés updated. And perhaps the only genuine revolution is that of those who remain dignified amid myth, poverty, and war.

And there lies the irony no newsroom dares confess: while the official narrative speaks of values, democracy, and dignity, the entire world monetizes suffering. Heroes die for the flag, the living open Patreon accounts, and the media trade tragedy like a Netflix series. The West weeps for Ukraine in high definition—but profits from its war in 4K. In the end, the only thing truly globalized is not freedom, but the ability to profit from it.

Sources:

· Die Welt (2023) “In den Bordellen sind es mittlerweile etwa 50 Ukrainerinnen.” — Link: https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/plus253481548/Prostitution-In-den-Bordellen-sind-es-mittlerweile-etwa-50-Ukrainerinnen.html

· Eurasia Review. Prostitution: An Unwanted Brand of Contemporary Ukraine. https://www.eurasiareview.com/11042023-prostitution-an-unwanted-brand-of-contemporary-ukraine-analysis

· FactCheck.org. Social Media Posts Make Unsupported Claims About Zelensky’s Income and Net Worth. https://www.factcheck.org/2022/07/social-media-posts-make-unsupported-claims-about-zelenskys-income-net-worth

· KVINFO (2023). Ukraine: Gender Stereotypes Insight Report. https://kvinfo.dk/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Ukraine_Gender-Stereotypes_Insight_2023.pdf

· Kyiv Independent. Zelensky Publishes Declaration of 2024 Family Income. https://kyivindependent.com/zelensky-publishes-declaration-of-2024-family-income

· Kyiv Independent. Zelensky Publishes Declaration of 2024 Family Income. 30 mar 2024. https://kyivindependent.com/zelensky-publishes-declaration-of-2024-family-income

· Livemint. From Comedian to President: 5 Surprising Facts About Volodymyr Zelensky’s Net Worth and Properties. https://www.livemint.com/news/world/from-comedian-to-president-5-surprising-facts-about-ukraines-president-volodymyr-zelensky-net-worth-and-properties-11740962554561.html

· MythDetector. How Did Zelenskyy’s and Ivanishvili’s Wealth Change During the Russia-Ukraine War? https://mythdetector.com/en/change-during-the-russia-ukraine-war

· OCCRP (Pandora Papers). Pandora Papers Reveal Offshore Holdings of Ukrainian President and His Inner Circle. https://www.occrp.org/en/project/the-pandora-papers/pandora-papers-reveal-offshore-holdings-of-ukrainian-president-and-his-inner-circle

· Rapid Gender Analysis of Ukraine (UN Women, 2022). https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2022/05/rapid-gender-analysis-of-ukraine

· Reuters. Ukraine’s Zelenskiy Reports His Income Increased in 2022. 29 mar 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraines-zelenskiy-reports-his-income-increased-2022-2024-03-29

· TAMPEP (2012). National Mapping on Sex Work – Ukraine. https://tampep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Final-Mapping-Report-Ukraine-ENG.pdf

· The Washington Post. Ukrainian Officials Charged in Defense Procurement Corruption Scandal. 11 ago 2025. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/08/11/ukraine-defense-corruption

· Work on Poverty/Unemployment in Ukraine. Obrizan, Maksym. Poverty, Unemployment and Displacement in Ukraine: three months into the war. arXiv preprint, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.05628